Training your team to make independent decisions

“It was like the debate of a group of savages as to how to extract a screw from a piece of wood. Accustomed only to nails, they had made one effort to pull out the screw by main force, and now that it had failed, they were devising methods of applying more force still, of obtaining more efficient pincers, of using levers and fulcrums so that more men could bring their strength to bear.”

… wrote C.S. Forester about British Generals during World War I. The German Generals felt the same way:

‘The English Generals are wanting in strategy. We should have no chance if they possessed as much science as their officers and men have of courage and bravery. They are lions led by donkeys.”

… said German general Erich Ludendorff, per Evelyn, Princess Blücher, in her memoir published in 1921.

Fortunately, by the 1940s, the British Army was catching on to German ‘strategy’. The Germans depended decentralized decision making and flexibility in the fog of war, not on rigid implementation of battle plans devised by generals¹.

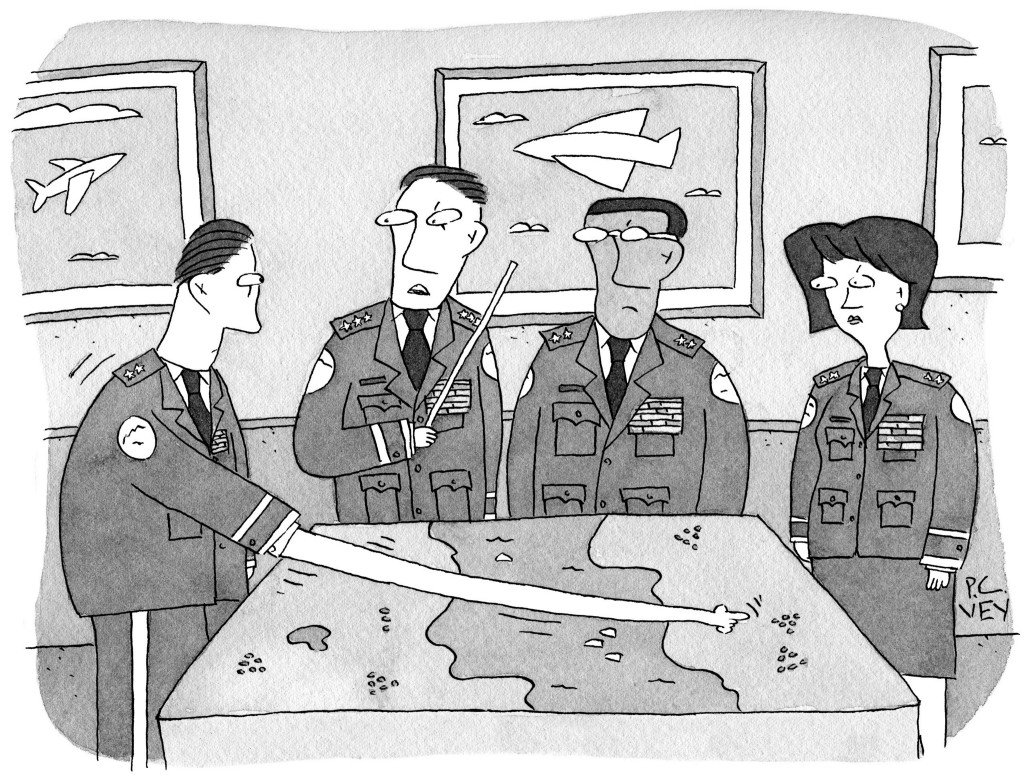

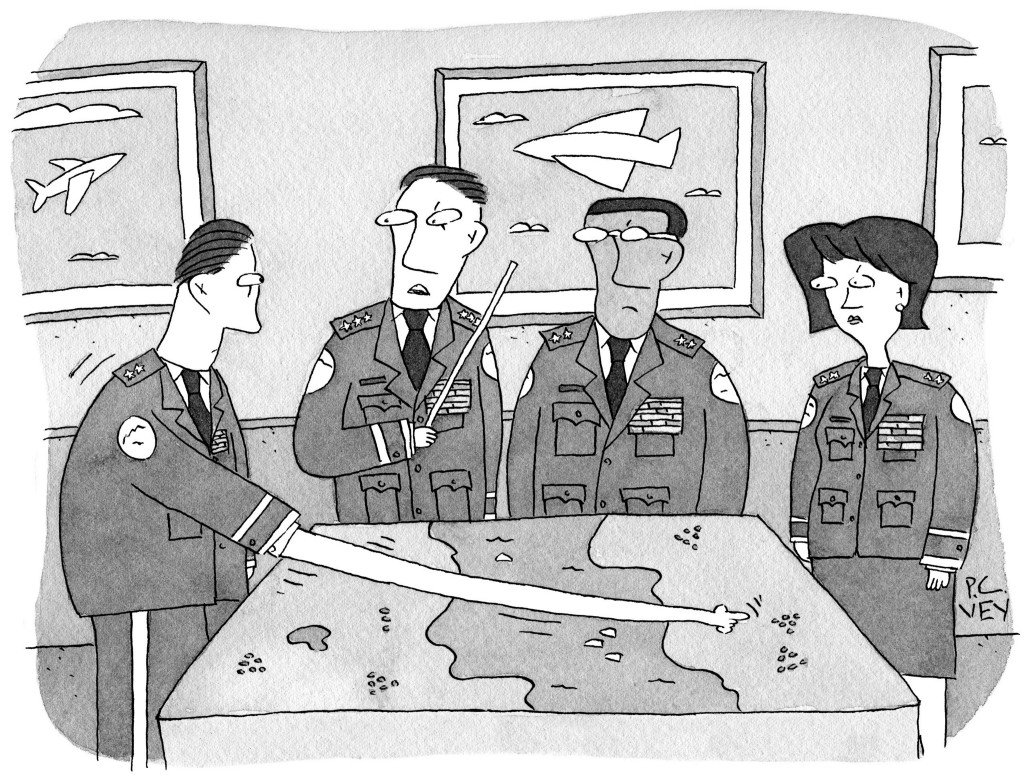

Generals are humans too

Most product development today still remains in the hands of product ‘generals’ who want to build detailed plans and roadmaps. And they’re usually well-intentioned, just trying to do ‘the right thing’. But without timely data that can disconfirm their convictions, product generals can be wrong for a long time.

People who are right a lot, they listen a lot, and people who are right a lot, change their mind a lot.

People who are right seek to dis-confirm their most profoundly-held convictions, which is very unnatural for humans.

- Jeff Bezos

On the other hand, individuals working on the front-line have the most accurate and timely data on what’s working and what’s not. Good generals know that their job is to set the direction, train the team, and let the team figure out how to get there.

Training the Team

I wish more folks shared how they train their teams and operationalize independent decision making. Here’s my short list.

1. Build a shared understanding of business

At the highest level, this includes defining the key business drivers, an evolving set of product metrics that measure these drivers, and the checks + balances (guardrails) that signal possible over-indexing on one measure².

At a deeper level, shared understanding emphasizes gathering signals of gaps/blind spots from diverse sources of data: a deep dive analysis on experimental data, anecdotes from customer support, insights from user research, direct customer conversations, and so on.

Mechanisms that allow any individual to raise unexpected signals in a joint forum serve a critical purpose. These mechanisms (a) help new members develop a shared vocabulary and mental model for recognized patterns, (b) bring everyone up to speed on patterns that are expected vs. not in the emerging situation, and (c ) allow everyone to help understand and address the issue³.

Make it weekly operational review or a daily briefing, depending on the urgency of the situation and how fast it’s evolving. Whatever it is, give everyone a way to pull the cord!

2. Create the ability to safely take risks

Starting with first principles… the smaller the change, the smaller the risk; the more reversible the change, the lower the stakes. Three working principles that I rely on heavily:

Break down large projects/goals into small experiments, then double down on what works

Make it trivial to test a change with a small section of users, and progressively expand the blast radius; for example, start by dog-fooding features with internal employees, then open up to a small group customers, say, who asked for the feature, then expand more broadly

Use reliable tools to roll back with ease when things don’t go as expected

Creating a safe zone for taking risks and building a culture of experimentation takes ongoing effort and persistence. Start with one team, publish their results, and make them your heroes!

3. Invest in timely and accurate data that’s accessible to everyone

Specifically, invest in tools that can up-level everyone without requiring a degree in data science. Pave the way for everyone to dive deeper into the data and arrive at the same conclusions. Whether an engineer or a PM looks at data, the tools should arm them with the same insights as a data scientist.

Similarly, an engineer shouldn’t need someone to tell her that her work is not showing results. If she tries something and doesn’t see the metric moving, she should move on to trying something herself without being told that she’s off course.

4. Iterate fast

At Statsig, we iterate relentlessly to discover what really matters to our customers. Few teams realize that execution speed is a low hanging fruit in this journey of discovery. Dan Luu has been eloquent about this:

It’s fairly easy to find low hanging fruit on “execution speed” and not so easy to find low hanging fruit on “having better ideas”.

However, it’s possible, to simulate someone who has better ideas than me by being able to quickly try out and discard ideas (I also work on having better ideas, but I think it makes sense to go after the easier high ROI wins that are available as well).

Being able to try out ideas quickly also improves the rate at which I can improve at having better ideas since a key part of that is building intuition by getting feedback on what works.

This isn’t an exhaustive list on how to be ‘right a lot’ by any means. But with a lot of help from my super smart Statsig team, it keeps me out of trouble!

If you’ve got a story on how you changed your mind about a product assumption, drop a comment here, or join me on the Statsig Slack channel.

[1] U.S. Army’s Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) describes the German practice of Auftragstaktik (literally, mission-type tactics):

“Commanders issue subordinate commanders a clearly defined goal, the resources to accomplish the goal, and a time frame to accomplish the goal. Subordinate commanders are then given the freedom to plan and execute their mission within the higher commander’s intent.

During execution, Auftragstaktik demanded a bias for action within the commander’s intent, and required leaders to adapt to the situation as they personally saw it, even if their decisions violated previous guidance or directives.

To operate effectively under this style of command requires a common approach to operations, and subordinates who are competent and trained in independent decision making”

To my Amazon eyes, this read like a primitive version of the popular leadership principles!

[2] When Facebook detected declining engagement in 2018 H1, they concluded that they’d been over-indexing on time-spent on the platform. They decided to pivot “meaningful social interactions” (MSIs) as the core metric in 2018 H2. According to CNN, in 2019 the company’s ranking team concluded that optimizing for MSI “was no longer an effective tactic for growing sessions” and that “public-content ranking was a ‘better strategy’.” Even in the biggest businesses, metrics are an ever-evolving balancing match!

[3] As in Japanese plants, where every worker is empowered to stop the assembly line, the team may temporarily slow down but it eventually starts to generate stronger results as they gain experience root causing and fixing core issues.